“The property which every man has in his own labour, as it is the original foundation of all other property, so it is the most sacred and inviolable”

Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith

Key takeaways

- Companies categorise roles into job functions and grade levels, which results in salary bands

- Salaries (and bands) are reviewed annually as part of the annual budgeting and performance review process

- Salary bands are revised based on benchmark data, financial performance and macroeconomic forecasts

- Budgets cascade downwards into individual teams, with the manager of the team deciding how to allocate the salary increments and bonus allocations

Introduction

Welcome to the second post in my Salary Series! In my first post, I wrote about the structural issues that cause persistently low salaries in Malaysia.

In this post, I want to share insights on how companies determine employee salaries. From the process by which companies set and review salaries to the key factors behind each role’s salary.

Once you understand what goes on behind the scenes, you will uncover a whole new meta-strategy to increase your salary when negotiating, job hopping and pivoting careers.

I write this based on my own career experience progressing to C-1 level positions, serving as a manager with the authority to decide salary and bonuses, participating in budget reviews, negotiating my salary, and gaining insights from many relevant professionals in the recruitment industry.

Standardising employee salaries

Disclaimer: The processes and approaches I describe here are generalised for simplicity. The process can vary by type of company, size, industry, business model, and other factors. For example, professional services firms are even more structured and rigid, whereas a 20-person startup may not have any policies or processes at all. From now on, most of what I describe will depict what happens in a top-tier multinational corporation.

In large corporations, employees are usually categorised into certain levels/grades and functions. This makes it easier to measure and compare employees against each other, as well as categorise employees based on the function they serve.

Generally, employees are classified in the organisation structure according to:

- Job function: This is related to your technical skillset. For example, accounting, marketing, software engineering, sales, etc.

- Grade level/seniority: Where you rank in the hierarchy of the organisation. From a lowly peon to the CEO, companies generally divide employees into hierarchical levels

- Revenue/profit centres vs cost centres: Certain departments and functions are known as revenue/profit centres, and others, cost centres.

- Revenue/cost centres are considered the revenue-generating part of the company, and generally own the P&L breakdown of the company.

- Examples are Sales teams, Frontline teams, Commercial, Business Development and/or Product teams.

- If your department has a P&L accountability, you’re in a revenue/profit centre. These areas of the company, on average, have higher salaries than other departments.

- Other departments are considered enablers or support/shared functions and are categorised as Cost Centres. Some examples are HR, Legal, Compliance, Technology, etc.

- Interestingly, functions typically seen as cost centres can become the revenue centres for certain industries; for example, in a law firm, the lawyers are the ones generating the revenue

- Compensation structure: Depending on your role and seniority, your salary may be structured differently, for example:

- Hourly / Monthly salaries – Most employees are paid in this manner

- Commission – Sales employees generally receive commission payments based on the volume of sales they bring in

- Long-term Incentives – This is usually in the form of restricted stocks, options, long-term bonuses and Employee Share Schemes. Typically for senior management and early employees in startups

We’ll focus on monthly salaries, as that normally makes up 90% of your salary and is the most meaningful to understand.

For an orderly compensation structure (to ease decision making and ensure consistency), companies will categorise roles into grade levels and functions. For each grade level, a “salary band” is assigned, that is, a range of salaries with an upper and lower limit specific for that grade level. An example of what this might look like is below:

If you’re wondering what the last column is (Performance onus max threshold), we’ll talk about that more later in this post when we cover bonus allocations.

Salary bands and bonus allocation review process

Again, let me reiterate the disclaimer: Timings, process steps, and other specific details may vary for each company.

For large corporations, the fundamental principles of the approach below will be consistent (and then, smaller companies may have some but not all of these policies and processes).

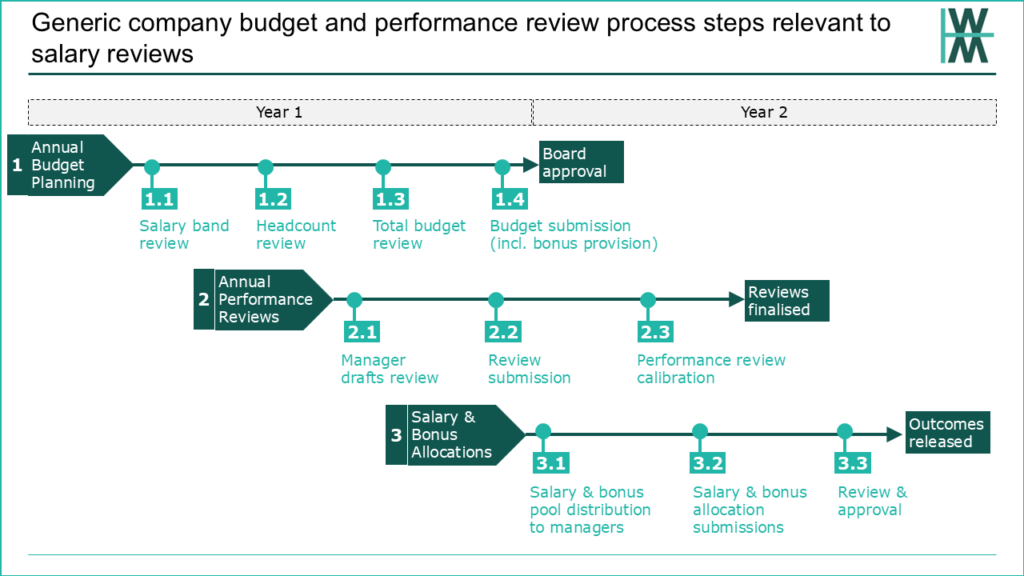

The graphic below is an overview of the various processes relevant to salary reviews and bonus allocations.

Let me break down and explain each step in the process.

1.0 Annual budget planning

Every large company goes through an annual budget planning cycle. Finance teams, with Management teams, will forecast the next financial year’s revenues and costs. This translates to a holistic budget for the next year. It dictates the maximum limit a company is allowed to spend to achieve a proposed revenue target.

1.1 Salary band reviews

Every year, Human Resource (HR) departments will (or should) propose updated salary band figures for each grade level. How does HR determine what the bands should be? Generally, it depends on:

- External benchmark data – Companies pay good sums of money to procure salary benchmarking data. Where do they get them from?

- You know those salary reports and guides that you can find online, issued by recruitment firms and employment marketplaces? They collect a huge amount of data from candidates looking for new jobs, as well as from job postings from their customers (employers). These companies use that data and sell far more detailed versions of these reports to companies for benchmarking purposes.

- In scenarios where more rigorous analysis/review of the salary bands is required, a company may even hire an HR consulting firm. They come with compensation specialists who will analyse existing and recommend adjusted salary bands according to the company’s objectives. Which brings us to…

- Company compensation policy – Some companies have explicit (but confidential) policies.

- These policies may outline the compensation strategy to compensate employees within the range typical for the industry/function. It’s not so simple because you have to balance controlling costs, but also attracting talent.

- An example of a remuneration policy for a top-tier tech company might be to pay salaries that are within the 70th to 90th percentile of the comparable positions across tech companies globally, with an objective to attract the best talent

- Revenue centres vs cost centres – Many companies remunerate revenue centres higher than cost centres (as mentioned earlier), even at the same grade level. This is because revenue centres are typically viewed as the core business of the company that “bring in the business”, a.k.a. biggest value

- Business and financial performance – The stronger the business financially and in the market, the more financial flexibility the company has to pay higher salaries and be competitive in the employment marketplace

- Macroeconomic situation – If there’s a recession or other headwinds, a company may choose to reduce the salary increments which they may grant. The more uncertainty, the more buffers the company may want to have to limit expenses

1.2 Headcount review

Managers will provide their inputs on their headcount requirements for the next financial year, based on anticipated volumes of work and business targets.

Although this doesn’t directly affect salaries, it is a vital input to calculate employee expenses (headcount multiplied by cost per employee) and ensure it doesn’t increase too much (unless necessary, e.g. high growth phase of the company).

Aside from the salary band reviews by HR, managers (or whoever is involved in the process) will discuss with Finance and HR on the aggregated level of salary increases for existing staff. Meaning, salary increases are viewed at a macro level (division/company-wide), not at an individual level.

As an example, the budget might end up having a 5% increase in existing personnel costs company-wide (3% for inflation, 2% for high performers on aggregate). It is at this juncture that managers need to anticipate how much salary increase they need to ask (and justify) for their teams.

Note: This can happen a lot earlier than you might expect. When some of you are thinking of asking your boss for a raise during your 1-on-1 annual performance review discussion, the budgeting process may have already passed this stage. This is another key point in the negotiating process, which I’ll cover in future posts.

1.3 Total budget review

The total company budget (comprising revenue and expense targets) in its entirety is reviewed by the Senior Leadership Team with Finance. Budget allocations are refined to ensure that the forecast revenue and expenses are aligned. For example, managers of sales teams need to justify why they need additional sales headcount, i.e. to grow sales in an untapped geographical area, which then comes with an associated target revenue goal in the budget to justify the extra expenses.

1.4 Budget submission (incl. bonus submission)

In large corporations, Finance and (Senior) Management submit the budget to the Board, which is then responsible for approving the budget. Once the budget is approved, Management (CEO and below) will then execute the budget plans accordingly, and generally cannot exceed the approved budget limits without obtaining the Board’s approval. Bear in mind, there can be exceptions to exceed budget limits, but require exception approvals (up to Board level, depending on expense threshold).

The Budget will include new headcount requested (which translates to new hires), as well as total expected personnel cost expenditures. In some companies, allocations for bonus provisions may be included as part of the Budget or might be a separate submission (the financial year reporting process to the Board).

2.0 Annual performance reviews

Around the same time as the budget review (just before the end of the financial year), annual performance reviews are conducted. The outcomes of the reviews serve as important data points to guide salary increments and bonus allocations.

2.1 Manager draft review

Managers conduct performance reviews for each of their team members. At many companies, the manager will conduct an initial review with the staff before reviews are finalised.

2.2 Manager review submission

Managers submit the performance review with an indicative or proposed performance rating for their staff.

2.3 Performance review calibration

Managers (or senior management only), with HR, assess the overall distribution of performance ratings to ensure consistency (eliminate bias or non-standardisation of review criteria), as well as normalise ratings to fit a bell curve. This means, only a small number of employees would get the highest ratings (and vice versa).

All large corporations calibrate performance ratings to varying degrees. Any company that claims publicly not to do this is doing it in the background. All corporations need to categorise employees into their superstars, “average” and underperforming employees. How else do they know who they want to retain, motivate, reward and promote? No company will allow a manager to rate every single one of their direct reports as a superstar performer.

3.0 Salary increments and bonus allocations

Remember during the annual Budget process, the board had approved the new financial year’s personnel costs and bonus allocations?

Now, in the new financial year, since the budget has been approved, management can proceed to increase salaries and pay bonuses.

3.1 Salary & bonus pool distribution to managers

On a high level, these become two pools of expenses to allocate, which is cascaded and split into the various divisions, departments and teams, depending on the company’s delegated authority, at which managerial level decides on the allocation to individuals. In many companies, this would be the department head or your direct manager.

So, how does it work? Again, it varies across companies, but it’s something like this:

Salary increment pool

- Let’s use the earlier example of the 5% company-wide salary increment. This amount is then broken down to the department/team level (for simplicity, let’s assume the 5% is applied similarly across all departments and teams, although this isn’t always the case in reality)

- If you’re a manager with 4 staff with annual salaries totalling ~RM480k (about RM10k p.m. per employee), you will now be given a total of RM24k (RM480k * 5%) to distribute as you please

- As an example: You could give 3 employees the base 3% “inflation increase” (RM300 p.m. per employee), and give the remainder RM1,100 p.m. to the high performer (resulting in an 11% salary increase).

- Now, there are certain guidelines and policies which would prohibit the manager from just allocating all RM25k to one employee (unless justified, i.e. the other 3 were seriously underperforming), and most of the times, most managers are quite fair to distribute this evenly (to keep the peace), except deciding to give extra increments to the better performers (or, if biased, to the employees they like the best)

- Some companies may not have a salary increment pool, and work from the bottom up. This means that managers proactively nominate the salary increase for each team member, and as long as the total salaries do not exceed the approved budget (alongside fair distribution policies), it will be approved

- Depending on the company, there are requirements to ensure that all employees are within the upper and lower salary bands for their grade, so that would mean a manager cannot allocate more salary increments to breach the ceiling, and sometimes employees that fall under the lower bands (when revised upwards) might get an automatic increase to their salary

Bonus allocation pool

- Bonus pools act in a similar way to salary increment pools; however have even more variance in how it is broken down into constituent bonus pools

- This is because at the Board level, only the total bonus amount is approved (for non-C-suite employees). The breakdown of who gets how much is left to the discretion of the Management.

- The total bonus pool is typically divided among the divisions/business units based on the performance of that division as a whole. The better performing divisions are allocated a higher proportion of the bonus, and underperforming divisions get less (after considering factors such as revenue vs cost centres, etc)

- Within a division, the further breakdown into department bonus pools is determined the same way, with more allocations to better-performing departments than others

- This breakdown of the pool continues until we reach the smallest unit of a “team”, where the manager of that team (department head, team manager, etc) has the delegated authority to propose or allocate bonuses to individual employees

- Remember the first table above, there was a performance bonus threshold? Some companies have policies that limit the amount of bonus one individual can be allocated from the pool (as a % of their annual salary, or a monthly salary multiple)

3.2 Salary increment and bonus allocation submissions

The proposed salary increments are submitted by the respective managers to provide a consolidated view of adjustments and allocations for Senior Management to review and approve

3.3 Review & Approval

Senior management, with HR, will review the salary increments and bonus allocations.

Normally, it is a sanity check to ensure that it meets or is under the approved budget amounts, and that there are no irregularities (e.g. large sums of bonuses given to underperforming employees, salary adjustments are justified and not skewed, no salaries are above or below bands, etc).

Once approved, outcomes are finalised, and managers are meant to communicate the salary increments and bonuses to employees.

Notable differences in the process that is practised in Malaysia

Some personal observations where the process differs from the “best practice”, particularly from “non-top-tier, non-global companies” (a very polite way of describing the companies I’m talking about), are below. These are due to the culture, ingrained habits, ways of working or structural dynamics of the local market.

Lower salary bands mean nothing, but the upper band is a hard limit. Some companies with salary bands for each grade level treat the lower salary band as a “recommendation” instead of a hard salary floor. Hiring managers in these companies may recruit new hires at the lowest possible salary, even if it is below the salary band assigned to that role.

Lack of calibration. Some companies do not have “calibration sessions” amongst managers to ensure fair and consistent performance reviews. Calibration amongst peers is the best way to ensure consistency of performance outcomes to standard criteria, so adjustments are made to ensure ratings are fair and bias is minimised.

Excessive hierarchy. Some companies I’ve seen have up to 20 or more grade levels! I’m not sure in what instances a company needs 20+ grade levels, but the literature on organisational strategy shows that 20+ layers/levels of hierarchy is suboptimal. This can result in…

Significant overlapping of salary bands. Ever heard of some more senior team members (or even managers) getting paid less than more junior members of a team? This arises when companies offer salaries way below salary bands, or the salary bands themselves have a lot of overlap. Might as well not have salary bands if that is the case.

What does this mean for you?

Now that you understand the process of salary increments (and bonus allocations), there are a few implications for how you should think about salary negotiations.

Start salary discussions early. By the time you have a performance review discussion, the budget might already be finalised. And the budget determines how much managers can increase salaries by. If you haven’t talked to your manager during or before budget planning, your manager may not have asked for an increased budget for higher salary increments.

Budgets determine potential salary increments. Once budgets are finalised, it’s a zero-sum game. At this point in the game, your manager (or whoever has the authority to decide) will have to balance the amount of increments each person gets with others in the same team.

Your manager may not be the decision maker. The person who ultimately decides the team/department salary budget might be someone more senior than your manager. In these instances, your manager will have to champion your salary increment request to obtain the approval (whether that’s via the budgeting process or the exceptions process). So knowing and winning over the decision maker is critical.

Exceptions outside the standard process can happen, but it’s an uphill battle. Typically, any exception requests outside of approved budgets require approvals which go higher up the chain, so the bar is higher. Avoid going the exception route if possible.

FAQ

Why don’t companies pay everyone the same salary if they are the same grade level?

In the corporate world, it’s just not possible to pay two people who do the same job the same salary, and apply this principle to all roles across a company. The reality is, everyone’s experience and circumstances are different. Some people join a role with 6 years of experience, some people with 9 years. Some people just negotiate better.

Even if you did that as a starting point, it’s going to deviate after the first performance review. Some people will perform better than others and hence get better performance ratings, which should result in different salary increments.

Why do companies pay new hires higher than their existing loyal staff who have proven themselves?

I don’t think this is always true. It could be, it may not. I’d love for someone with holistic, detailed data to unpack this. There are lots of cases where this happens, but there can be a lot of cases where new hires are paid less than existing staff (or else where did the idea of employers lowballing offers come from? Some people would still be accepting these lowball offers, because of the oversupply of graduates pushing salaries downward).

I think this idea came about because when many people job hop, they can get a ~20%-30% increase, so it is natural to infer that the job hopper is now getting 20-30% higher than the average existing employee in the new company. But what if the job hopper was getting paid 30-40% less in the previous company? What if it’s a step-up promotion that the job hopper is getting?

I’m not aware of anyone having sufficient objective data to make a firm conclusion.

What happens when I ask for a raise outside of the annual cycle?

If the company highly values you and your manager is willing to fight for you, your manager will propose your case for an exception approval. Whoever has the delegated authority to approve such exceptions will need to review your request. Depending on the company, this might be a difficult process to near impossible, especially if Budgets are already set and your team has already reached the Budget threshold. But of course, it’s assessed against the cost of lost productivity, time and resources spent on finding your replacement if you leave.

I would advise waiting for the right time, instead of trying to fight against the tide.

My manager claims that only his/her boss can approve salary increments. My request for a raise was rejected, and there’s nothing my manager could do. Is my manager just making excuses?

Not all managers have the authority to determine salary increases and bonus allocations. You need to confirm if it is your manager’s manager has the authority, and if not, uncover what the actual approval process is. Identifying the decision maker will be key to successful negotiations (if the approver is a C-suite and they’ve never heard your name, good luck). More on this in my next post on salary negotiations.

My company claims it does not adjust performance ratings to fit a bell curve

That claim is a marketing gimmick to attract talent.

Does your company have a rating system for performance reviews? Even a 3-point rating scale will have calibrations to ensure a bell curve distribution of performance ratings. The fact is, most employee performance is always compared to peers. How else would a company identify the top talent for promotions? How can you be sure that you and all your peers receive the same amount of increments and bonuses?

No company will allow a manager to rate all of their team members with the highest rating. It will be calibrated and adjusted to a bell curve.

Will attaining a Master’s or other postgraduate degree mean I will receive a higher salary?

All things being equal, no.

You cannot command more just by having a postgraduate degree. There might be some scenarios where this may happen, but it’s not common. I’ve just never come across a situation where someone has tried to negotiate a salary based on his/her postgraduate degree and succeeded in getting a meaningful increment. And to me, as a hiring manager, that’s not a valid reason. That just means you might know more theory, but it’s meaningless as a case for a higher salary. (Note: I do have a Master’s, but I did not ask for a higher salary using my Master’s as a justification; there are other reasons to pursue a Master’s)

Khazanah Research Institute did some research (albeit a bit dated, 2018) that shows the range of salaries offered for new hires, and it appears that postgraduates don’t fare significantly better than undergraduates. Perhaps it’s due to the significant oversupply of graduates.

Wrapping Up

If you weren’t aware (before reading this post) how a company determines annual budgets, salary increments and bonus allocations, I hope this is insightful. Some of you reading this might wonder why it is important to know how the process works behind the scenes.

Trust me, it’s important and extremely useful to understand who the decision-makers are and the opportune times to make your move. This helps you develop the right strategy to get that salary increase.

More on that and actually how to negotiate your salary in my next post. I’ll be sharing very detailed, step-by-step information that isn’t widely shared anywhere else. Stay tuned.